Due to overwhelming requests (Hi Clint, Hi Jack, Hi Mel, Hi Quentin), we have decided to upload the text of our hard-to-find 1983 tribute to Diana Rigg’s portrayal of Emma Peel in TV’s The Avengers. This appeared in two issues of Dave Rogers’ fanzine On Target…The Avengers (nos. 3 and 4). (It appears on eBay from time to time at £14.99 for each issue!) This was probably the first serious attempt at critical discussion of Rigg’s portrayal; there have in recent years been a number of books that tackle the subject, of course.

Our boss John B. Murray is one of those tragic males who never recovered from the impact of Diana Rigg on TV during adolescence, many of whom have approached Diana Rigg in their middle age and told her of their feelings, to her considerable irritation.

Mr. Murray claims he studiously avoided doing this when finally meeting her after a lifetime of waiting. (There had been three near-misses in the past, particularly when Murray went to see Michael Hordern, her old partner in Stoppard’s Jumpers, in a revival of Trelawny Of The Wells and, as is his wont, he went to the bar in the interval, only to find Diana Rigg sitting at a table. Clearly, his jaw must have dropped, metaphorically, and she noticed this and gave him a stare that could freeze the blood at twenty paces. He got the message and slunk away, crestfallen.)

Despite Murray’s boast of what a civilised meeting it was (the fool even thinks she liked him, because she asked him about his work), here in the editorial office we all suspect she probably still thought “What a jerk!“….We even put this to him once when he annoyed us by staying in the pub all day when we had deadlines to meet and Murray mused: “Makes one want to write a philosophical treatise on the intricacies of the relationship between star and devoted fan…or it would if they did not keep showing time-sapping re-runs of Columbo on TV every day…”

Dave Rogers, who published the very first books on The Avengers, wrote in his Editorial in “Emma Peel Special” No. 4: “My, my, it appears that my ruse in using the John B. Murray ‘Essence of Emma Peel’ article has paid dividends. I confess to having thought twice before running this piece intact, i.e. unedited. It is, after all, very long and somewhat ‘heavy’ in parts. However, I did so in an attempt to generate some much needed feedback from our readers – and it’s worked! Letters have been pouring into the O.T. mailbox at a very brisk rate and it would appear that most of you are in favour of the article. However, one or two letters were critical – with one reader going so far as to call the feature ‘junk’, so I’ve decided to allow Mr Murray to reply personally to that criticism and his comments will be printed soon.”

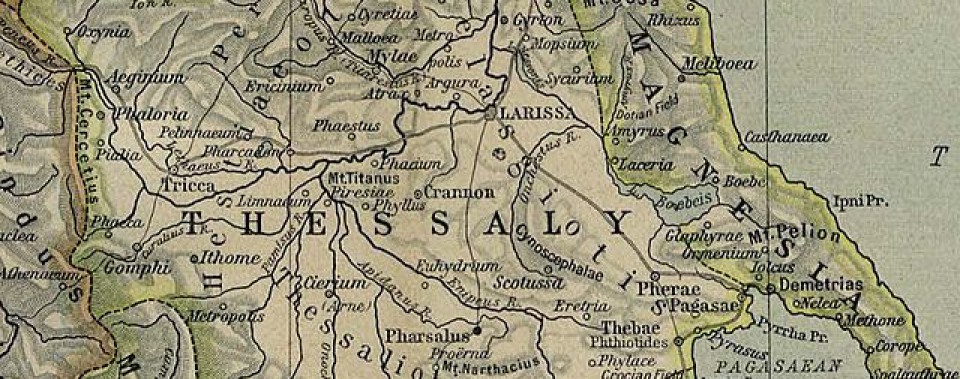

We, the underpaid and overworked editorial staff of Thessaly Press, could not find any evidence that Murray had replied to this foul calumny in print, despite poring through our dog-eared copies of On Target…The Avengers, so we sent unpaid Hungarian intern Kata trawling the pubs of Knightsbridge

to find the Managing Editor for an explanation. She eventually found him having a long liquid lunch in The Nag’s Head and, after a bit of flirtatious banter (Murray is known to have a weakness for voluptuous Eastern European sirens), he consented to an exclusive interview:

“Unfortunately, I never did reply to that criticism, as I was busy furtively scouring London’s soft porn cinemas, like the Curzon Harringay at Turnpike Lane – a terrible fleapit that is now an African Christian Church by some weird irony…if only they knew what used to go on there! – for rare showings of Christina Lindberg movies.”

“She had made a big impact on some of us by starring for 18 months in Leicester Square in Exposed, in which she was incredibly appealing, but other movies like What Schoolgirls Don’t Tell and What Are You Doing After the Orgy? (surely one of the great film titles of all time!) required visits to far-flung cinematic emporia and the wearing of a soiled raincoat.”

“I could never have dreamed that, one day far in the future, a gentleman named Quentin Tarantino would confer cultural kudos and respectability on her body of work. At the time I must confess I was not thinking about her body of work. I had seen her in Penthouse magazine (where Michael Caine was photographed chatting her up at the Penthouse Club) and I suspect it was just her body I was thinking of…”

“However, I did send a copy of Emma Peel And The Essence Of Charm to Diana Rigg, who, as is usual, did not respond. Later, in the 1990s, I proposed a biography of Diana Rigg which a leading U.K. publisher green-lighted (after I had written 80 pages) on condition she would co-operate, but she declined the offer. I should have chosen Christina. I would have had a clear field back then.”

“I finally met Diana Rigg at an event at the Victoria and Albert Museum in February 2012 and she could not have been nicer, signing for me a Hungarian magazine from February 1964 which she confirmed was probably her first magazine cover, predating The Avengers (it was occasioned by a tour by the Royal Shakespeare Company when she was a member; she was photographed playing Adriana in The Comedy Of Errors).”

“I was too diplomatic to mention Emma Peel And The Essence Of Charm or the aborted biography, afraid she might give me that Emma Peel stare of hers that can freeze a man’s blood. Clearly she does not suffer fools gladly. But I took the one opportunity that presented itself to connect with her, because she had talked about working with Vincent Price on Theatre of Blood at the event, which was an interview with critic Al Senter. She recalled giggling because, below the view of the camera, Price in full Shakespearean outfit was wearing slippers, due to bunions! And she told the familiar story of how she got Price and actress Coral Browne together, acting as a go-between. She encouraged Coral Browne, in the privacy of the ladies’ room, to go for it when Coral mentioned she fancied Vincent Price and she advised Price when he told her that he did not know what to give Coral for her birthday: ‘Vincent, you have it about your person!'”

“I must confess this slightly naughty banter nearly gave me the courage to ask her to verify a story I heard about Theatre of Blood. According to this story, which may be apocryphal, Rigg was lying flat out on the floor between ‘takes’, due to having injured her back when the acrobats in Tom Stoppard’s stage play Jumpers, in which she starred as Dottie alongside a magnificent Michael Hordern, lifted her bodily into the air but accidentally dropped her onto the stage, leaving her with a chronic bad back. Allegedly, Price stood beside her and said ‘Diana, when you lie there like that, you need fucking!’ But things had been going so nicely, I could not risk incurring her displeasure. I guess I’ll never know the truth.”

“So I used the Vincent Price connection to offer her our Michael Reeves book, to which Price contributed some comments, and our Brett Halsey book, as he was a personal friend of Price and made two films with him. Regrettably, I never heard back from her, as I expected…but hope she liked them! I still regard her as the finest actress I have ever seen on stage, maybe also on film. I will never forget the first night (actually the first public preview rather than the official first night) of Jumpers at the Old Vic in 1972, in which she was radiant, when she accidentally dropped some mashed potato down her cleavage…and erupted into a heavenly smile!”

At that point, an increasingly expansive Murray ordered another round of drinks and Kata never came back to the office that afternoon…

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

EMMA PEEL AND THE ESSENCE OF CHARM: A Critical Appraisal by John B. Murray

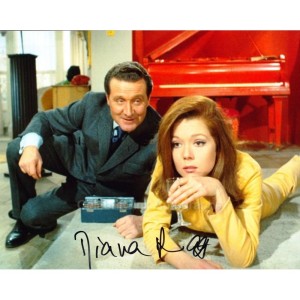

Diana Rigg’s ‘Emma Peel’ deserves serious analysis and appraisal both as an influential cultural icon, i.e. a symbol of the confident new womanhood of the Swinging Sixties, and as possibly the most beloved heroine in the history of British television. Yet articles on Rigg’s acting career accord it relatively little kudos, usually deeming it rather elementary fare that gave her the popularity for her more prestigious later work in the classics. But those of us who followed this sustained performance for two and a half years at an impressionable age will never forget it. Emma Peel is graven in our hearts. So what was the essence of her charm?

Emma Peel’s vitality as a screen heroine arose from the shifting reality of contradictions in her being. These contradictions were inevitable, given the casting of a gentle/intellectual actress like Rigg in a violent/physical role such as Cathy Gale’s successor (Diana Rigg replaced Honor Blackman’s Cathy Gale as the female lead of The Avengers). Honor Blackman played Gale with an aggressiveness that many felt to be latently lesbian but the very casting of Rigg ensured a more light-hearted approach. For ABC-TV’s Drama Casting Director, Miss Dodo Watts, put her up for the part because of her humour, as she once explained: “At the Shakespeare season at Stratford-on-Avon, I saw a tall, dark and lovely girl playing Adriana in The Comedy Of Errors. Her comedy touch was so delightful that I made a note of her in my special files.” It is significant that at the initial audition the producer Brian Clemens and Rigg herself both felt she was unsuitable. Simply casting Rigg (who replaced the less humorous Elizabeth Shepherd, who was cast first and then rejected) offset the hardness of the role with a delicious irony and femininity that scripting alone could not achieve.

Rigg’s instant acclaim in the role eventually permitted her to resolve some of the more overt contradictions in Emma Peel, but many of the complexities remained basic. For male viewers, Rigg’s Emma was essentially representing the duality of femininity itself, which Stephen Heath in Screen (Autumn 1978) has defined: “Woman’s order is that of the double: duality of sexual organs (clitoris, vagina), duality of the relation to the mother (the woman is of the same sex as the parent who bears her), duality in her doubling-loss of herself as one (menstruation, childbirth).” Emma’s principal duality is that of the disjunction in her nature between animalism and intellectualism (between Avenging assignments, Emma published learned articles on maths and science). Emma’s most distinctive appeal is the subsumption (but not eradication) of her animalistic nature in sophistication. In certain poses, that animalism is apparent: as our still photograph reveals, in a moment of fear or alarm, Emma’s lips pout, presenting a direct erotic challenge to the male.

The presentation of this animal power is all the more effective for the strength of the sophisticated intellect which usually suppresses it. Rigg’s Emma is ‘an Amazon’ (as her publicity put it), but an Amazon brimming with delicate eroticism, for she is too intellectual not to be subtle about her physical needs.

A further duality is her embodiment of ‘good’ and ‘evil’, which yet permits morally consistent behaviour. Evil? In a sense, yes. Any woman prepared to kill without remorse – particularly a beautiful, cultivated one – is unnatural in British society to a degree that is almost perverse. Emma Peel also frequently uses sex (wickedly, perhaps, to prudish sensibilities) to tantalise: in A Touch of Brimstone, she represented ‘The Queen Of Sin’!

Indeed, the series uniquely and notoriously exploited a strange erotic undercurrent that barely stopped short of fetishism: the alluring young woman in black leather wrestling with men, Steed occasionally smacking or patting her bottom because he could not resist doing so (e.g. with his rapier in their very first screen encounter in The Town Of No Return),

a black-corseted, spiky-collared, kinky booted Emma being whipped by Peter Wyngarde in A Touch Of Brimstone (a scene heavily censored from the British print after a Press furore), Emma walking in completely soaking wet clothing after a struggle in the river in You Have Just Been Murdered, etc. The overall duality was summed up by the credit sequence juxtaposition of guns and flowers. Lethal and lovely – love and death intertwined – the prettiest black widow.

Rigg’s less-than-total identification with all aspects of the role was expressed in a tentativeness that soon diminished as her confidence increased, and the blossoming of her persona throughout the span of her involvement in The Avengers is something wondrous to behold: from the tentative sidekick of episodes like Silent Dust (1965) to the headstrong, confidently mocking woman of The Fear Merchants (1967). Richard Holliss (Starburst) has claimed that in the early episodes she was “a slightly scatter-brained school-girl type”. (This quality sometimes surfaces in later episodes, e.g. at the end of Epic she mistakenly clobbers Steed and in horror she clasps her hand over her mouth in wide-eyed schoolgirl fashion). True, but certainly a highly eroticised schoolgirl, with her black leather and mini-skirts, and the overtly challenging threat of her kung-fu (long before the world had ever heard of Bruce Lee). It was an extraordinarily potent mix, and a very British combination of the erotic, fetishistic and sado-masochistic with elements of innocence and respectability (Steed always addressed her as “Mrs. Peel”, virtually never as “Emma”). Little wonder that Diana Rigg was surfeited with proposals of marriage from adolescent boys, for whom she perhaps created the blueprint of the ideal mate.

Eventually, Rigg emancipated Emma from some of the more obvious elements of male fantasy, rejecting the leather gear (explaining “It wasn’t me. It belong to Cathy Gale.”) for feminine fashions and toning down the wrestling in favour of humour (intellectual but still erotic-based, of a knowing, winking kind). This shift to a more feminine heroine – without sacrifice of the character’s pioneering spirit of female independence – was accomplished when Rigg’s vastly increasing confidence in the role began to assert itself. This confidence is accountable for the remarkable stylistic shifts in her performance between Silent Dust and The Fear Merchants, for example. In the former, Rigg very much underplays, reacting blankly to information in her early outdoor scenes – not that this is aesthetically unpleasing, one should hasten to add, for Rigg’s early appearances as Emma Peel have an undeniable naive charm, far less often encountered in her later more polished performances.  In those, she becomes much more assertive and ironical in terms of mocking facial attitudes – mocking even her own awareness of her beauty (“Do you find her attractive?” she teases Steed with false disdain as he looks at her replica in Never Never Say Die). This overt confidence in her relationship with Steed, whom Patrick Macnee (who played Steed) today claims was Emma’s lover, virtually created the obvious double entendre in Steed’s remark “For services rendered” when he gives her a box of chocolates in her flat at the end of Never Never Say Die. The Joker, like the earlier The House That Jack Built an extended solo showcase for Rigg, reveals the degree to which, with eye movements and facial expressiveness, Rigg had become comfortable at communicating with the camera: even today, this episode exhibits a greater command of the film medium than most of her subsequent cinema films.

In those, she becomes much more assertive and ironical in terms of mocking facial attitudes – mocking even her own awareness of her beauty (“Do you find her attractive?” she teases Steed with false disdain as he looks at her replica in Never Never Say Die). This overt confidence in her relationship with Steed, whom Patrick Macnee (who played Steed) today claims was Emma’s lover, virtually created the obvious double entendre in Steed’s remark “For services rendered” when he gives her a box of chocolates in her flat at the end of Never Never Say Die. The Joker, like the earlier The House That Jack Built an extended solo showcase for Rigg, reveals the degree to which, with eye movements and facial expressiveness, Rigg had become comfortable at communicating with the camera: even today, this episode exhibits a greater command of the film medium than most of her subsequent cinema films.

The confidence of Rigg’s Emma was, of course, also part and parcel of the confidence of Sixties’ Britain, and as Emma Peel was economically independent of men (daughter of shipping magnate Sir John Knight, widow of a test pilot), it almost seemed natural that she should also be independent of them in other ways – socially, sexually, spiritually, intellectually. She paved the way for Angie Dickinson’s Police Woman and other forceful heroines, if not for Emmanuelle and other sexually liberated heroines. It is perhaps unfortunate that Sixties’ censorship (to which she fell victim more than once: her Dance of the Seven Veils in one episode was banned by U.S. television) did not allow Emma an on-screen sex life. Rigg dealt with this by making Emma’s attractions romantic rather than provocative, which in a way achieved a peculiar kind of anti-voyeurism in male viewers. Seeing Emma disrobed was most disconcerting as it violated the romantic intimacy of the weekly rendezvous. Intimacy is the key note here. The continual facial close-ups favoured by television directors brought the viewer closer to Emma (both physically and figuratively) – particularly when she was in peril – than is usual with cinema heroines and created an hitherto unique rapport with male viewers. It was the strange situation in which Emma may have been the utmost male erotic fantasy,

(daughter of shipping magnate Sir John Knight, widow of a test pilot), it almost seemed natural that she should also be independent of them in other ways – socially, sexually, spiritually, intellectually. She paved the way for Angie Dickinson’s Police Woman and other forceful heroines, if not for Emmanuelle and other sexually liberated heroines. It is perhaps unfortunate that Sixties’ censorship (to which she fell victim more than once: her Dance of the Seven Veils in one episode was banned by U.S. television) did not allow Emma an on-screen sex life. Rigg dealt with this by making Emma’s attractions romantic rather than provocative, which in a way achieved a peculiar kind of anti-voyeurism in male viewers. Seeing Emma disrobed was most disconcerting as it violated the romantic intimacy of the weekly rendezvous. Intimacy is the key note here. The continual facial close-ups favoured by television directors brought the viewer closer to Emma (both physically and figuratively) – particularly when she was in peril – than is usual with cinema heroines and created an hitherto unique rapport with male viewers. It was the strange situation in which Emma may have been the utmost male erotic fantasy, but Rigg’s humanity so intimately presented gave her an extraordinary reality, evoking paternalistic feelings in male viewers. Although in her words and attitudes Emma forcefully expressed pre-feminist independence (note her uncalled-for, slightly sarcastic rebuttal of Steed after their car accident in The Hour That Never Was when Steed mentions that he had travelled that road a hundred times during the war: “Since you know it so well, it’s remarkable you couldn’t stay on it”), her actions often belie this tough attitude. Her actual behaviour reveals – almost despite herself – a touching vulnerability that serves to make her usual bravery all the more touching, e.g. she clings to Steed for reassurance when following him along the cavernous tunnels of the underground bunkers in The Town Of No Return. Similarly, her girlish protestation that Steed did not fight fair during their fencing match in the same episode is highly endearing.

but Rigg’s humanity so intimately presented gave her an extraordinary reality, evoking paternalistic feelings in male viewers. Although in her words and attitudes Emma forcefully expressed pre-feminist independence (note her uncalled-for, slightly sarcastic rebuttal of Steed after their car accident in The Hour That Never Was when Steed mentions that he had travelled that road a hundred times during the war: “Since you know it so well, it’s remarkable you couldn’t stay on it”), her actions often belie this tough attitude. Her actual behaviour reveals – almost despite herself – a touching vulnerability that serves to make her usual bravery all the more touching, e.g. she clings to Steed for reassurance when following him along the cavernous tunnels of the underground bunkers in The Town Of No Return. Similarly, her girlish protestation that Steed did not fight fair during their fencing match in the same episode is highly endearing.

For Emma Peel’s eroticism is most powerful for being subtle. Although Emma appeared in titillatingly scanty costumes in some episodes and enjoyed many flattering compliments (e.g. from Peter Wyngarde in A Touch Of Brimstone and from Peter Cushing in Return Of The Cybernauts) as well as complicity in frequently suggestive talk with Steed (“That looks a bit droopy” she remarks of Steed’s costume sword at the fancy dress party in A Sense Of History; “Ah, wait till it’s challenged” quips Steed), she was nevertheless obviously too well brought-up not to be committed to propriety. For instance, she disapproves of a sexy pin-up photo she finds inside a college student’s desk in A Sense Of History, remarking with irony that she prefers students to be “innocent”. Indeed, the force behind the episode Who’s Who? lay in the contrast offered by showing an Emma Peel who was – through a diabolical brain switch – a hip-swinging, gum chewing, easy loving swinger!

In a scene from the full version of The Fear Merchants as screened at London’s Scala Cinema Club but edited out of the recent UK Channel Four transmission print, Emma discusses the case at hand matter of factly while engaged on her sculpture, until Steed caresses her bare foot with a feather. She immediately withdraws but without acknowledgement of his action – and carries on talking and sculpting matter of factly. However, this is not frigidity, but the reverse. To allow the existence of Steed’s playful overture could only have culminated in a bedroom scene, which would not have been permissible on the small screen in those days and would have also held up the plot. Mind you, there was an overt suggestion of bedroom activities in The Town Of No Return, when Steed says to Emma – then at the youngest point of her screen life, this being her ‘introductory’ episode (the first screened, though not the first filmed) – “Shouldn’t you be in bed?” Suggestive pause as she stares at him. “You have to be up early for school tomorrow.” (Emma was working undercover as a schoolteacher.) The rapid cut to the following morning suggests she shared her bed with Steed, and the scene gains from the added frisson of its ‘naughty schoolgirl’ overtones.

Yet it is in the subjective probings of her thoughts in The House That Jack Built that we experience the full impact of Emma’s screen sensuality. Emma is obviously highly-charged emotionally, but at the same time her femininity is exceedingly logical. Faced with perplexing and genuinely terrifying problems, she halts, and Rigg’s voice-over conveys Emma’s mental workings by means of which she combats panic: “Think. Puzzle it out.” And, of course, it is her logic that saves her. A woman of warmth and humour but able to subordinate her emotions to pure reason: yet she was no Lynda Carter Wonder Woman but expressed a vulnerability that drew the viewer to her. Notice how expressive Rigg is of Emma’s virtual brink of despair after receiving the electric shock towards the end of the episode.

The universality of Emma’s appeal to the television audience in the Sixties was made possible by a classlessness in her character. Emma was definitely Upper Class, yet there was no trace of snobbery apparent in her attitude or behaviour. Her elegance was in no way pernicious, and she had a sensitivity to literature and art (e.g. an intimate acquaintance with the works of Francis Thompson was exhibited in Silent Dust) not usually noticeable in the debutante mentality. This was refreshing, as class antagonisms were strongly felt in other television spy series of the period in Britain, e.g. in The Rat Catchers which pitted an Old Etonian millionaire against his frustrated grammar school partner. This universal appeal permitted Emma to become a sort of sexual symbol of the Sixties’ emancipated woman, and girls wanted to emulate her as badly as boys wanted to meet her in the flesh.

In conclusion, Rigg’s achievement was in eliciting a light-hearted quality that rendered the ‘Amazonian’ and the ‘schoolgirl’ sides of her nature compatible. Only this makes it acceptable for her to go from karate chop to pleasanterie and, even when delivered from traumatic experiences, become instantly kittenish. For Rigg gave Emma emotions that yielded to logic but a logic that is in itself emotionally feminine, so rendering her duality functional and depicting Emma as at once vulnerable yet self-reliant, confident yet self-mocking, and real in a surreal universe (the surreality of The Avengers is itself an interesting topic for examination). Which is still in television terms an unrivalled achievement, and a distillation of the heroic that constitutes the essence of charm.

ADDENDUM (2014):

The images used above for critical commentary belong to copyright owners Canal Plus. The text is the copyright of John B. Murray, but listen all you bloggers, fanzine editors, academic lecturers, pirates of the Caribbean, one-eyed jacks and assorted riff-raff, you can reproduce it without seeking permission, with Murray’s blessing, he doesn’t care. Because, at the end of the day, we’re all Marko. (“You what, mate?”) “We’re all Marko from Tropoja!” Goooood luck!

But if you’re ever passing the Connaught Hotel, you could drop in and pay off his bar bill. Cheers!

One final thing. In November 2011, just weeks before that historic meeting with Diana Rigg, Murray attended a 50th Birthday celebration of The Avengers at the Barbican. They screened one of the best Avengers episodes, the truly memorable The Hour That Never Was, a script inspired by the story of the Marie Celeste but set at an abandoned RAF base. It was directed by Gerry O’Hara who attended the celebration (there was never any prospect that Diana Rigg would, given her ambivalent attitude to the success of The Avengers). O’Hara was interviewed on stage and said it was one of the best scripts he had ever been offered and he tried to bring visual embellishments to the filming….a spinning bicycle wheel when there seems to be no one around….a building that aped the shape of Steed’s bowler hat…and so on. One could see that O’Hara’s creativity added enormous interest to the episode.

And he revealed that Diana Rigg was open to suggestion and if she liked it, she would do it, such as the walk on the parapet of Tykes Water Bridge, which allows an interesting tracking shot. If she did not like it, she would refuse to do it. He also said she was creative. In the scene where she and Steed enter an empty hangar and there is a podium, it was her idea to stand on the podium and do a mock address with regal hand gestures…an example of Rigg bringing humour to a scene. O’Hara also confirmed what Patrick Macnee has written, that he and Diana Rigg would work on the script together and invent moments between them that gave character to their relationship.

After the event, Mr. O’Hara was standing around waiting for his taxi and Murray took the opportunity to engage him in conversation. He said that Rigg was simply “a Yorkshire girl, a Yorkshire lass” and he could not have foreseen she would become this giant talent of the classical stage, but he did think she would go on to do greater things. He also revealed that during The Avengers he was a bachelor living in Chelsea, as was Patrick Macnee who lived in Swan Court, off the King’s Road, so they used to meet up for meals at a bistro (now long gone) that was opposite the current restaurant for ladies who lunch, Daphne’s. He said he had in recent years visited Palm Springs, where Macnee is retired, and met up with him and found him “just the same, the same guy he was in The Avengers”, he hadn’t changed at all.

Murray wondered why O’Hara did not direct more episodes than the two he did, given the quality of The Hour That Never Was, and O’Hara explained that unfortunately there was some ill feeling towards him from the producer Brian Clemens, as O’Hara had had a relationship with Clemens’ girlfriend some time in the past, before she was with Clemens. He did however praise Clemens as one of the finest dialogue writers in the business and recognised as such.

Murray would have liked to tell Diana Rigg what O’Hara had said about her just weeks earlier, but there was not enough time, as he also wanted to know from her where she got the confidence to give such a strong performance in what was only her first major TV appearance, a play called The Hothouse with Harry H. Corbett. (Corbett became famous as the son in TV’s Steptoe and Son but Rigg recalled that he was not a pleasant man to work with.) She revealed she was just winging it and was actually terrified. Now available on DVD, it has not been seen by Rigg, as she said it would be too alarming for her to watch!

ADDENDUM (2015):

R.I.P. the fantastic Brian Clemens and the irreplaceable Patrick Macnee. You will never be forgotten.